Through developing initiatives such as health clinics and food and education programmes, the BCI -- for a small organisation -- punches well above its weight. Through the tireless efforts of its founder and President, Sally Coxe, together with Michaelīs natural flair for making things happen in Africa's trying conditions, the BCI is striving to ensure the survival of bonobos in the Kokolopori forest and elsewhere. There may be as few as 5,000 to 15,000 bonobos left, and the greatest concentration of these remaining populations appears to be in Kokolopori.

While we witness first hand the results of the BCI's work to be positive and tangible, there is much still to be accomplished. At the village Luke, Phil, Michael and I take turns speaking through an interpreter to a packed public meeting with eight chiefs and around 200 villagers. We try to address their concerns that they should continue to benefit from any help coming to the area, not just bonobos. We realise that more vital work and funds are needed to build on the community participation in bonobo conservation already so admirably set in motion by the BCI.

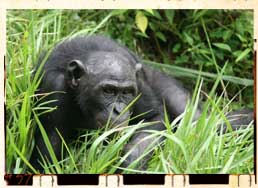

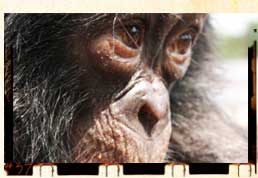

We spend a full week with the trackers. We observe, absorb and film the bonobos, at times only a dozen or so metres away. Each of us are moved, not from just our own watching, but the feeling also of being watched curiously by another conscious being. When a bonobo, from short range, looks you in the eye it is like holding up a mirror to humanity's own collective past. You are pervaded with the notion of not just knowing, but of somehow being known ... a connection, a commune however tenuous, with our own heritage -- a common ancestor 7 million years old -- and a sacred contract of trust once known between humans and the natural world that now largely lies breached and barely remembered.

One day, the bonobos having proved too fast to keep up with, Phil startles me with a tap on the shoulder while we're resting for lunch. I turn to see him pointing excitedly to a movement in the undergrowth no more than 15 metres away. We'd stopped tracking for 10 minutes or so, and an adult bonobo had returned as if to check on us. What makes Phil's sighting all the more striking was that the bonobo was walking past on two legs in waist high undergrowth, looking over his shoulder directly at Phil. So stunned and incredulous was he that initially Phil couldn't speak. He explains later that his first thought was that the bonobo was one of our trackers walking off into the forest to take a leak.

The frequent preference of bonobos for upright locomotion is yet another of their amazing attributes. It used to be thought that humans only began to walk upright when we left the forests for the savannah. Increased knowledge of bonobos extinguished that theory. The angle and alignment of the bonobo hip structure matches almost exactly that of our own two million year old ancestor, Australopithecus afarensis.

Perhaps of even greater significance to the essence of bonobo society than their sexual proclivities and bipedal capacity is the tenderness with which they nurture their young. Juveniles, even once weaned, will sometimes continue suckling until the age of six. Bonobo males remain deferential to their mothers for life, and derive their rank from where mum sits in the hierarchy.