The river is narrowing now and the current hastening, and the tiers of every green conceivable, relieved now and then by a splash of purple flowers in the crown of a tree, verge closer against us. Night navigation is increasingly difficult. We are awoken regularly by an abrupt crash and the sound of branches snapping as our vessel slams into riverside jungle. From each such mishap we collect a host of new insect life, awakening the next morning to also see spiders of all shapes and colours spinning webs across our quarters.

At last, and after narrowly avoiding a series of treacherous log-jams in the final stretches, we receive a rapturous welcome from the Kokolopori villagers. They'd made the trek through jungle to our disembarking point, and perhaps had been waiting for days for our arrival. Somehow word had been transmitted up river by "bush telegraph" -- villages still relay messages in this region through the beating of drums. The crowd of about 70 men, women and children, are each allocated a load of varying size. The heaviest (including partly full 44-gallon drums) are allocated to the older women who bear the burden like Nepalese porters with a strap over their foreheads.

We make an hour's march through lightly undulating rain forest, pleasantly free of dense undergrowth, and another few kilometres along a track to the village of Yalokole. The BCI, with the assistance of a grant I'd applied for from the Australian Great Ape Survival Project in 2003, have built a centre which forms the node for bonobo education and community development here. Glad to have made our destination, and full of keen anticipation to finally be in the land of bonobos, we turn in for an early night's rest in readiness for a 4am start with the trackers.

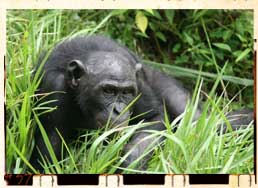

It's first light, and there -- high on the limbs of one of the emergent giants that fan like an umbrella over the canopy -- we see them. The bonobos -- part of a clan of 20 -- are rousing themselves from slumber in one of their favourite fruit trees. Phil, Luke and I, each covered in a sheen of sweat from our forest march on the heels of fleet footed trackers, can barely suppress our excitement. We talk in hushed tones and gaze through binoculars as the bonobos languidly munch on their forest treats no more than an arm's length away.

Their food rich habitat is one of the primary reasons bonobos enjoy an existence largely free of angst and competition. With such an abundance of fruits, nuts and edible plants the bonobos have all the more time and peace of mind to devote to socialising, grooming, play, or just rest and relaxation. The bonobos' diet is supplemented by invertebrates such as large insects, and occasionally small vertebrates they chance upon, such as the tiny forest duiker -- a miniature antelope. Unlike chimpanzees, which are known to hunt as a pack to kill monkeys and even other chimpanzees from neighbouring clans, the bonobos share their forest harmoniously with both other primates and adjacent bonobo groups. Scientists have even observed a bonobo female grooming a young red colobus monkey.

As the sun climbs higher and the morning mist dissipates, the bonobos start moving on, but not before we witness two females embrace face to face and acrobatically rub their vulvas together. Their sexual contact is brief, lasting no more than 10 seconds, and seems almost as perfunctory as a kiss on the cheek hello. One of the females then turns and presents to a nearby male and they mate missionary style for an equally short period. Having thus paid their reassuring morning greetings the bonobos move off swiftly through the canopy, and we fall in step behind our trackers trying to follow underneath them.