Thursday 17 November 2005

A more substantial welcome ceremony today. First another dance from the

Kokolopori Women's Association, led by a proud matron who called down the

blessings while the others chanted, clapped and swayed. About 20 women, the youngest about 18, the eldest completely indeterminate, and she would touchingly wipe the brow of the lead singer as she sung in her trance.

(Photo- Martin Bendeler)

The women were displaced by an army of schoolchildren that had amassed at the compound gates. Thousands coming in class by class, singing. BCI had brought a shipment of donated school supplies from the States and they were to be presented by the president of their main NGO partner here, Chief Albert Lokasola.

At one point there was almost a disastrous stampede over Bic pens before order was reestablished. Children also pleased for opportunity to gawp at white people. One boy had a t-shirt that I could have sworn had written on it, "honkeys steal my underwear at night". Later, on closer inspection, I saw it was "monkeys", not "honkeys" but I still prefer the former interpretation as a playful, post-modern critique of neocolonialism....

Honkeys steal my underwear at night- (Photo- Martin Bendeler)

Four men entered the clearing with drums and got down to business, and all the other men gathered around in a funky, shuffling circle. Some elders had prime position.

One haughty looking old fellow with a sour trout pout and a dead chicken on his head. Another elder in a tattered Western suit, sandals, and a shiny brass medallion of King Leopold of Belgium hanging proudly around his neck, a sad enduring reminder of how cheaply and easily that old tyrant bought and raped this country. The bafande, the shaman, was there, dignified in nothing but a loincloth and a crown of hornbills.

(Photo- Martin Bendeler)

We spoke with the shaman afterwards. He told of how a village ancestor was lost in the forest, stuck up a tree, and a bonobo came to his aid. At that point, Leonard, the head tracker came by to say that if we wanted to see the bonobos before they settled in for the night, then we'd better get cracking.

Paul got a lift to the start of the forest trail, about 5kms away, on Albert's motorbike

while I set off on foot with the trackers. Quickly had my typical pied piper entourage of children in my wake, walking along a sunny green trail. We turned off at the last

village, where forest trail led through manioc fields into light secondary forest. The frontier of the primary forest was guarded by a river of fire ants, who waited til they

had crawled up your trousers, down your socks and into your shirt before all stinging

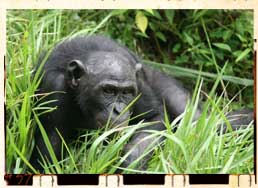

on invisible, inaudible cue. The bonobos have formidable guardians. The HaliHali

group of about 20 bonobos lived here. They are semi-habituated to humans, though if

you are particularly lucky they will throw dung at you in displeasure, though I would

rather receive dung from a bonobo than holy water from a priest...at least a bonobo is honest about his lecherous ways. Trackers had followed the group since dawn but

their trail would have taken us into a swamp where we could miss them if they backtracked up the ridge to set up their night nests. So we paused for awhile, Paul on

his fold-up safari chair, while the trackers fanned out to get a more immediate bearing. After about 20 minutes a tracker boy called out to say that the bonobos were

ready and waiting for us. Crashing indecorously through the forest, we found Leonard pointing to the sky. At first, I couldn't see anything but more forest until…

Way up high, at least 60m up, a bonobo swung from a leafless branch over to a

nearby tree to join his friends, who I could now see nestled in crooks, peering from trunks, and dangling from branches. Tapping his notebook, Leonard told us that he

had observations to make and that his team would look after us from here on in. With that, we aligned ourselves with the movements of the bonobos, excitedly scrambling

blindly over vines and logs with heads craned up in fixed awe. At one point, near a collection of old night nests, I counted eight bonobos, making the canopy sway and

shake with their acrobatics. The males appeared much more robust than I had been led to expect. Little wiry infants scaled branches with that fearless clumsy happy tummyout

insouciant way toddlers have of moving. At one point I heard something crashing with a heavy thud through the canopy to the forest floor and I immediately thought of

the Japanese proverb "saru mo ki kara ochiru- even monkeys fall from trees" and

needlessly worried for the bonobos' welfare. As it turns out, the bonobos leave a lot

more collateral damage in their wake than the nearby skinny monkeys with whom they share their great heights. I was initially worried a bonobo might shit on me, but

realised it was dislodged branches and logs I should be worried about. We followed them awhile longer, as they effortlessly Spider-Manned their way through the canopy,

gradually descending lower and lower. At one point I glimpsed a streak of black through a grove, all muscle and motion.

(Photo- Martin Bendeler)

We followed in pursuit, Leonard always 20ms ahead, notebook in hand, gliding

serenely and swiftly through the cluttered terrain as if God had appointed him an observer angel with divine laisser passer to discharge his single-minded duty. Leonard

had been tracking and recording the bonobos for many years, even the dark war years, when he had no support nor shoes nor flashlight. He wants to publish his finding next

year. The trackers followed the bonobo trail to an almost impenetrable thicket where we stopped to take stock of the time, the fading light, and the threatening thunder

trembling through the jungle valley. Leonard suggested we call it a day and head back, leaving a few trackers to mark out the bonobo sleeping quarters for tomorrow's

crew. BCI pays for the trackers to monitor and protect the bonobos every day, not just for when the rare white man wants to stumble through. Though we had only seen the

bonobos briefly, it was a fine introduction to what I'm sure will be a beautiful relationship. Within 15 minutes we were back in the cassava fields on our way to the

village. With perfect timing, darkness and rain fell as we arrived in the trackers’ hut, where we bought and distributed firewater in thanks and watched the lightning splash

across the jungle hills. When the rain eased we hit the village-trail on the long walk back. The path was a pale hint through lush foilage in the moonless clouded darkness,

with flickering faerie fireflies and lightning giving guidance. I set off carefree and infinitely pleased with my bonobo encounter but after awhile I became a little

concerned that no matter how fast I powerwalked, I had the surreal sensation of walking on a treadmill with only fireflies as points of reference in the darkness, I

began to think that we had overshot our mark and were marching swiftly ever further into the great jungle nothingness. I was freaking out a bit. Such is the night.

So pleased to finally see the electric lights of our compound that I did my own version of the happy-happy-joy song.

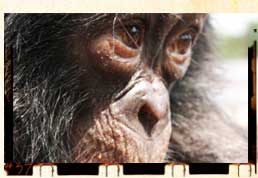

Miss Nina (Photo- Martin Bendeler)

Wonderful forest food of pineapples, papaya, bananas, plantains, lemons, liquid wild

honey that makes the local firewater palatable, hard-shelled bush oranges with juicy, sticky, sweet, grey, brain-shaped chunks. Freshly baked bread. A steady slaughter of

goats, pigs, chickens and ducks that have us feeling increasingly bloated and guilty. If I hear one more baby goat plaintively cry its last, I am irrevocably converting to

vegetarianism. I know now they call them kids because they cry like children.